ba space

In mathematics, the ba space  of an algebra of sets

of an algebra of sets  is the Banach space consisting of all bounded and finitely additive measures on

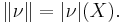

is the Banach space consisting of all bounded and finitely additive measures on  . The norm is defined as the variation, that is

. The norm is defined as the variation, that is  (Dunford & Schwartz 1958, IV.2.15)

(Dunford & Schwartz 1958, IV.2.15)

If Σ is a sigma-algebra, then the space  is defined as the subset of

is defined as the subset of  consisting of countably additive measures. (Dunford & Schwartz 1958, IV.2.16)

consisting of countably additive measures. (Dunford & Schwartz 1958, IV.2.16)

If X is a topological space, and Σ is the sigma-algebra of Borel sets in X, then  is the subspace of

is the subspace of  consisting of all regular Borel measures on X. (Dunford & Schwartz 1958, IV.2.17)

consisting of all regular Borel measures on X. (Dunford & Schwartz 1958, IV.2.17)

Properties

All three spaces are complete (they are Banach spaces) with respect to the same norm defined by the total variation, and thus  is a closed subset of

is a closed subset of  , and

, and  is a closed set of

is a closed set of  for Σ the algebra of Borel sets on X. The space of simple functions on

for Σ the algebra of Borel sets on X. The space of simple functions on  is dense in

is dense in  .

.

The ba space of the power set of the natural numbers, ba(2N), is often denoted as simply  and is isomorphic to the dual space of the ℓ∞ space.

and is isomorphic to the dual space of the ℓ∞ space.

Let B(Σ) be the space of bounded Σ-measurable functions, equipped with the uniform norm. Then ba(Σ) = B(Σ)* is the continuous dual space of B(Σ). This is due to Hildebrandt (1934) and Fichtenholtz & Kantorovich (1934). This is a kind of Riesz representation theorem which allows for a measure to be represented as a linear functional on measurable functions. In particular, this isomorphism allows one to define the integral with respect to a finitely additive measure (note that the usual Lebesgue integral requires countable additivity). This is due to Dunford & Schwartz (1958), and is often used to define the integral with respect to vector measures (Diestel & Uhl 1977, Chapter I), and especially vector-valued Radon measures.

The topological duality ba(Σ) = B(Σ)* is easy to see. There is an obvious algebraic duality between the vector space of all finitely additive measures σ on Σ and the vector space of simple functions. It is easy to check that the linear form induced by σ is continuous in the sup-norm iff σ is bounded, and the result follows since a linear form on the dense subspace of simple functions extends to an element of B(Σ)* iff it is continuous in the sup-norm.

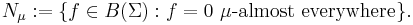

If Σ is a sigma-algebra and μ is a sigma-additive positive measure on Σ then the Lp space L∞(μ) endowed with the essential supremum norm is by definition the quotient space of B(Σ) by the closed subspace of bounded μ-null functions:

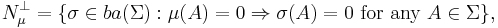

The dual Banach space L∞(μ)* is thus isomorphic to

i.e. the space of finitely additive signed measures on Σ that are absolutely continuous with respect to μ (μ-a.c. for short).

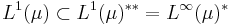

When the measure space is furthermore sigma-finite then L∞(μ) is in turn dual to L1(μ), which by the Radon–Nikodym theorem is identified with the set of all countably additive μ-a.c. measures. In other words the inclusion in the bidual

is isomorphic to the inclusion of the space of countably additive μ-a.c. bounded measures inside the space of all finitely additive μ-a.c. bounded measures.

References

- Diestel, Joseph (1984), Sequences and series in Banach spaces, Springer-Verlag, ISBN 0-387-90859-5, OCLC 9556781.

- Diestel, J.; Uhl, J.J. (1977), Vector measures, Mathematical Surveys, 15, American Mathematical Society.

- Dunford, N.; Schwartz, J.T. (1958), Linear operators, Part I, Wiley-Interscience.

- Hildebrandt, T.H. (1934), "On bounded functional operations", Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 36 (4): 868–875, doi:10.2307/1989829, JSTOR 1989829.

- Fichtenholz, G; Kantorovich, L.V. (1934), "Sur les opérationes linéaires dans l'espace des fonctions bornées", Studia Mathematica 5: 69–98.

- Yosida, K; Hewitt, E (1952), "Finitely additive measures", Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 72 (1): 46–66, doi:10.2307/1990654, JSTOR 1990654.